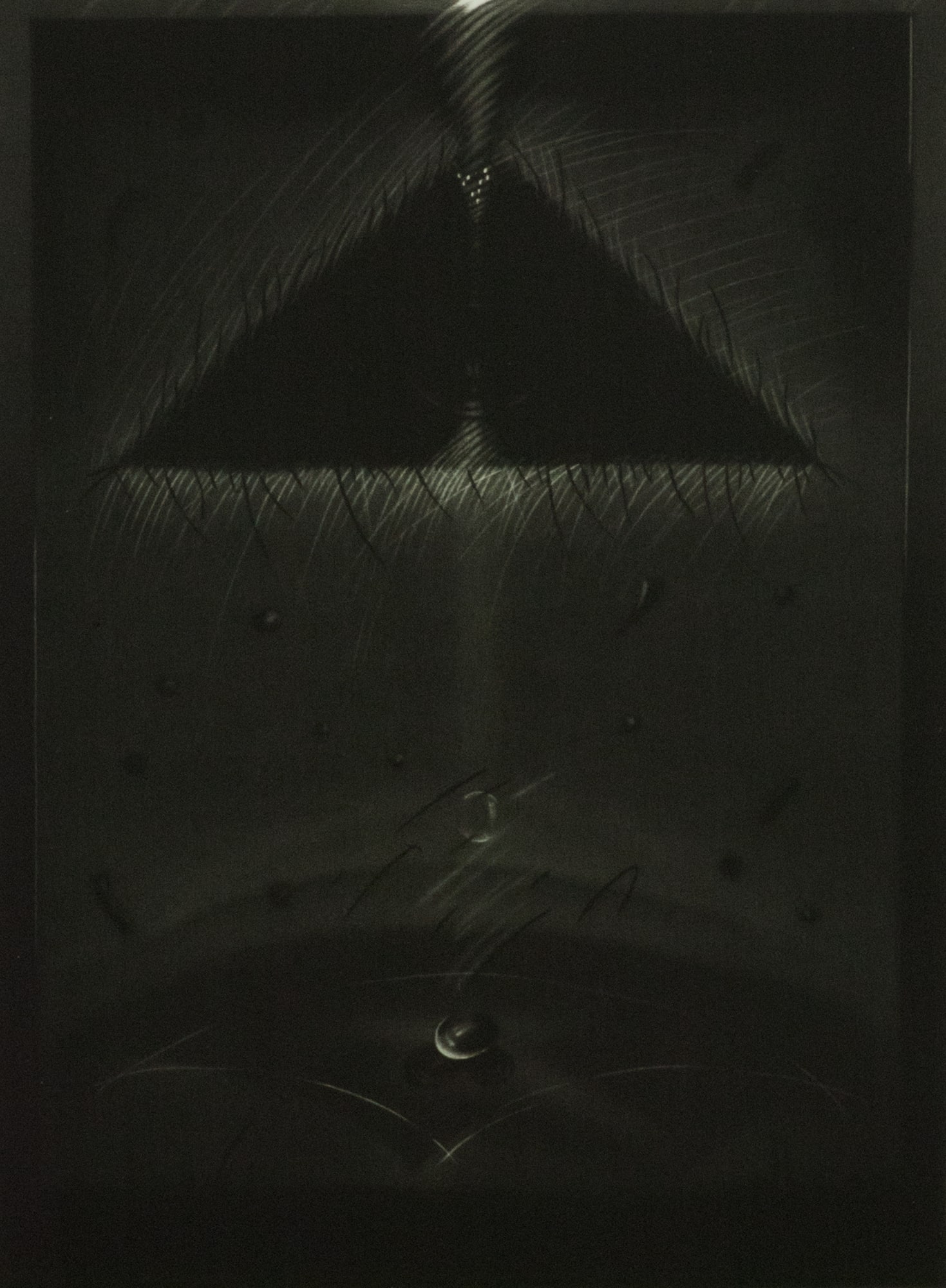

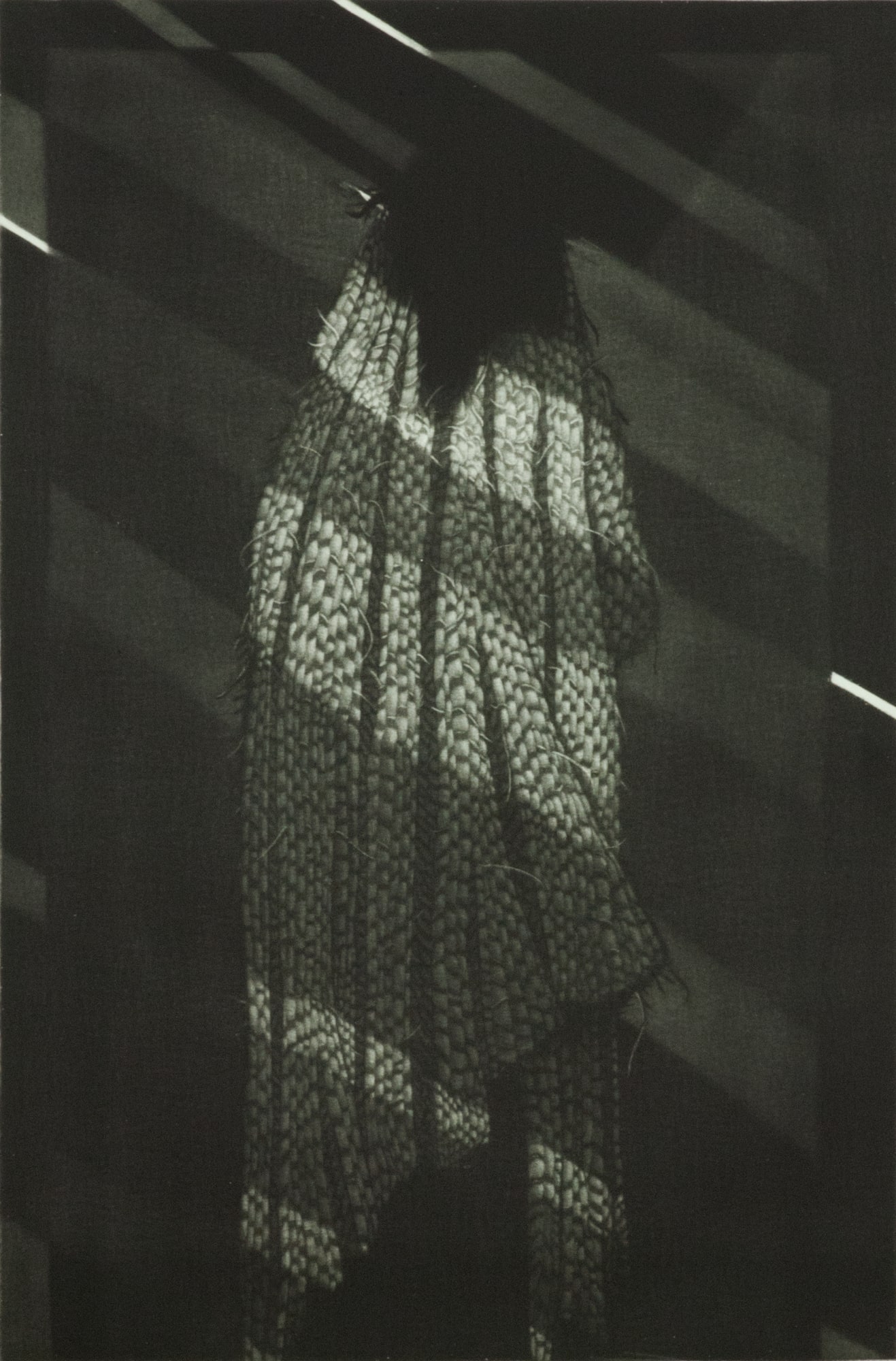

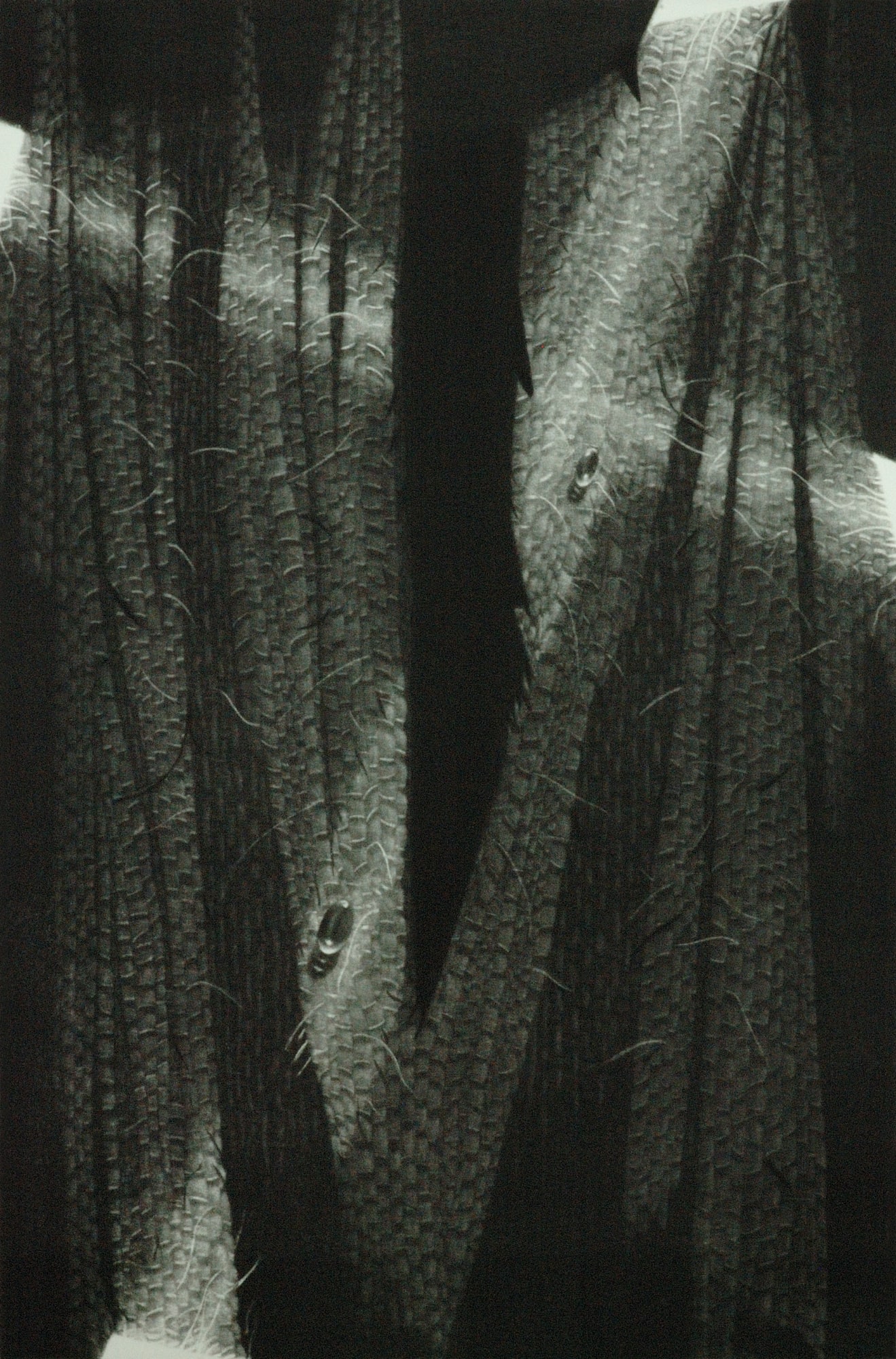

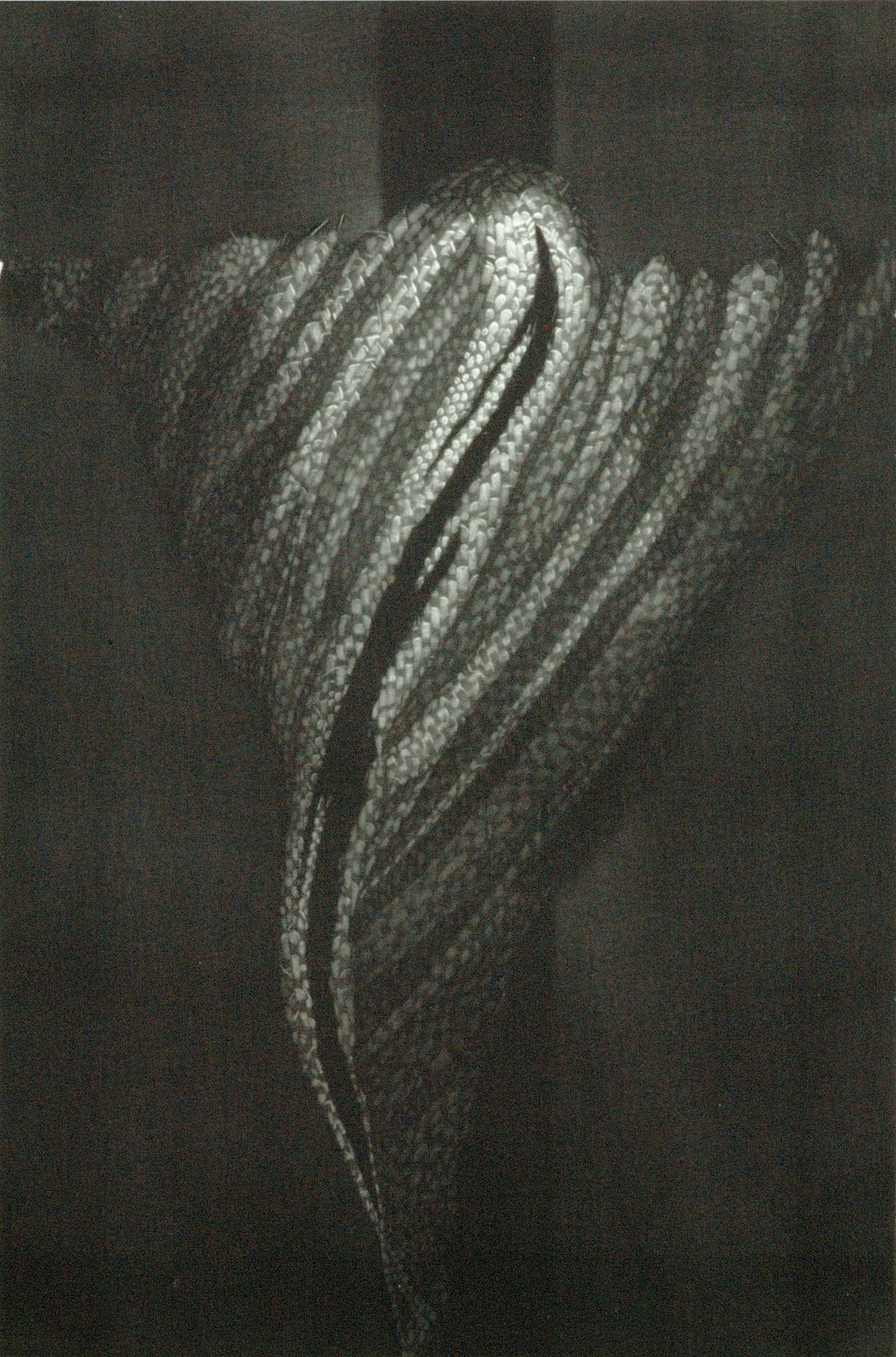

Malgorzata Zurakowska

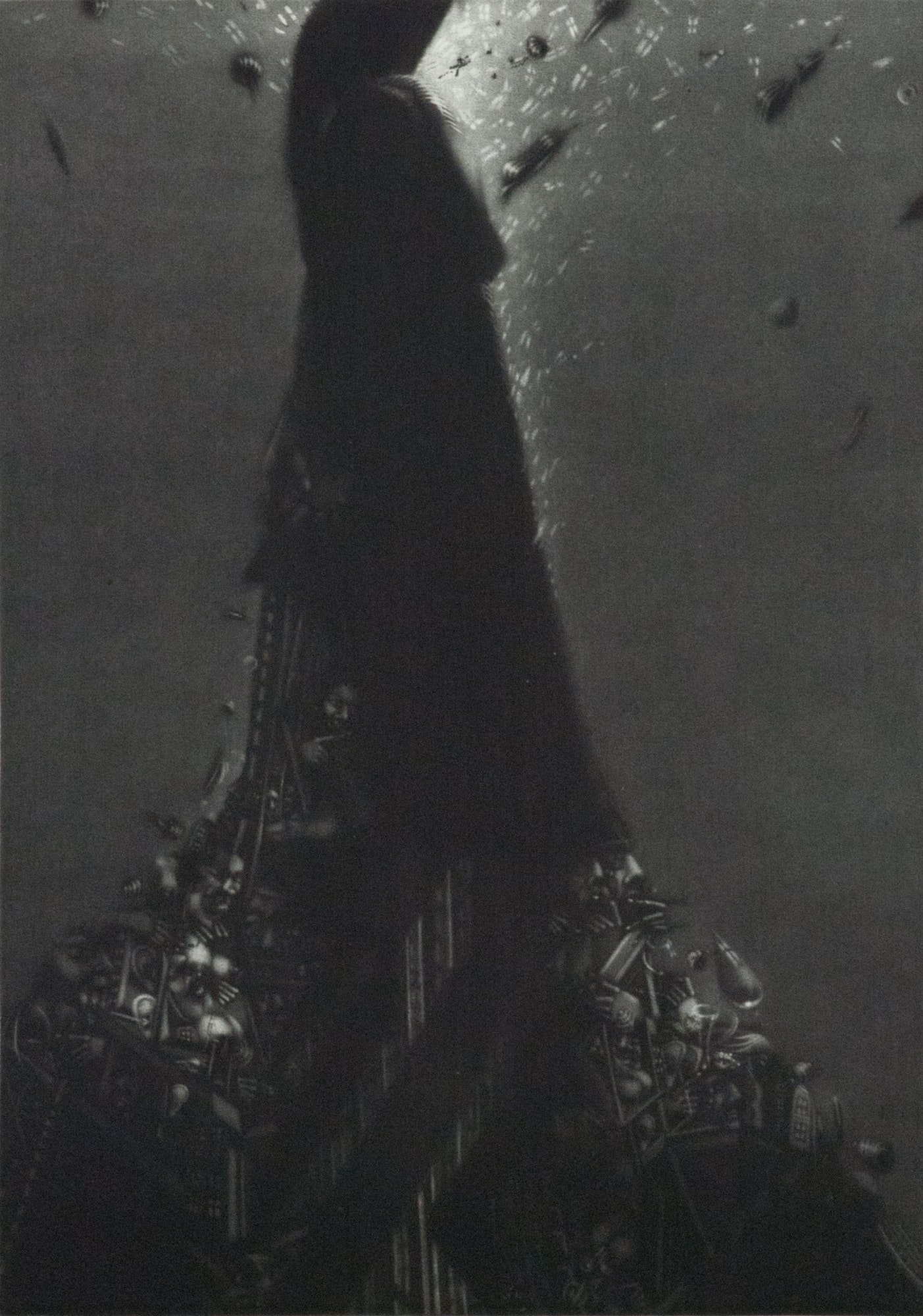

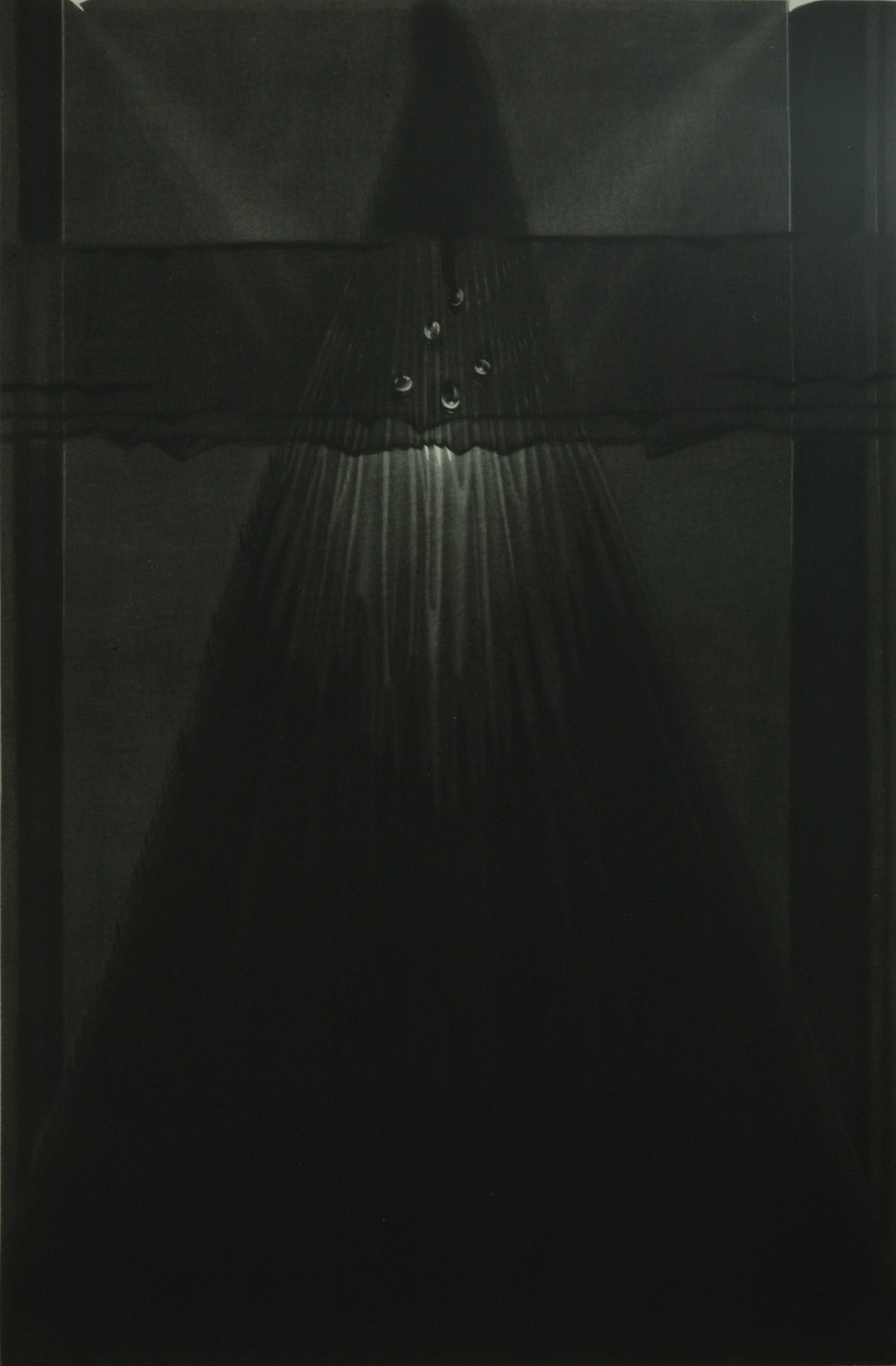

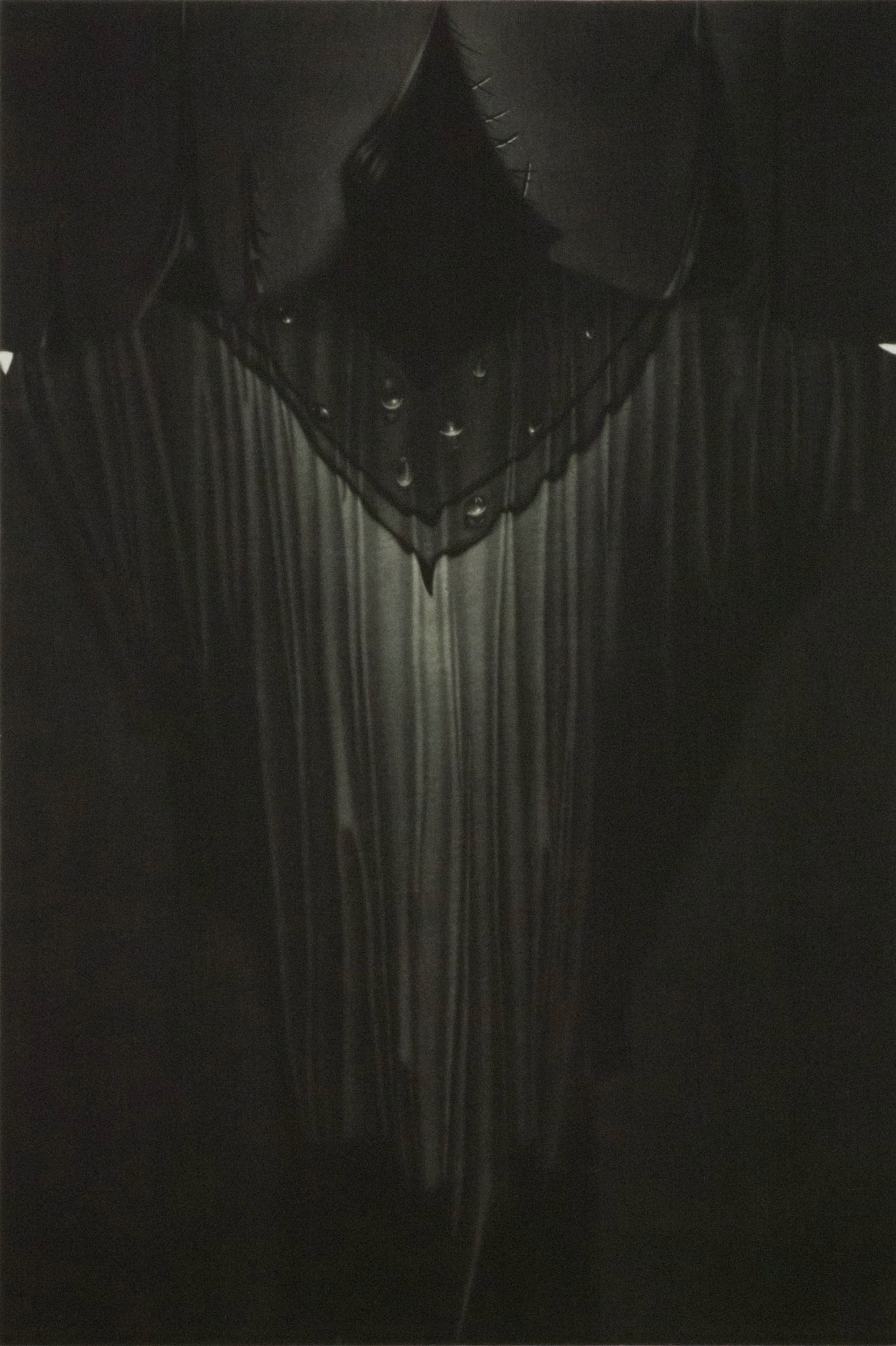

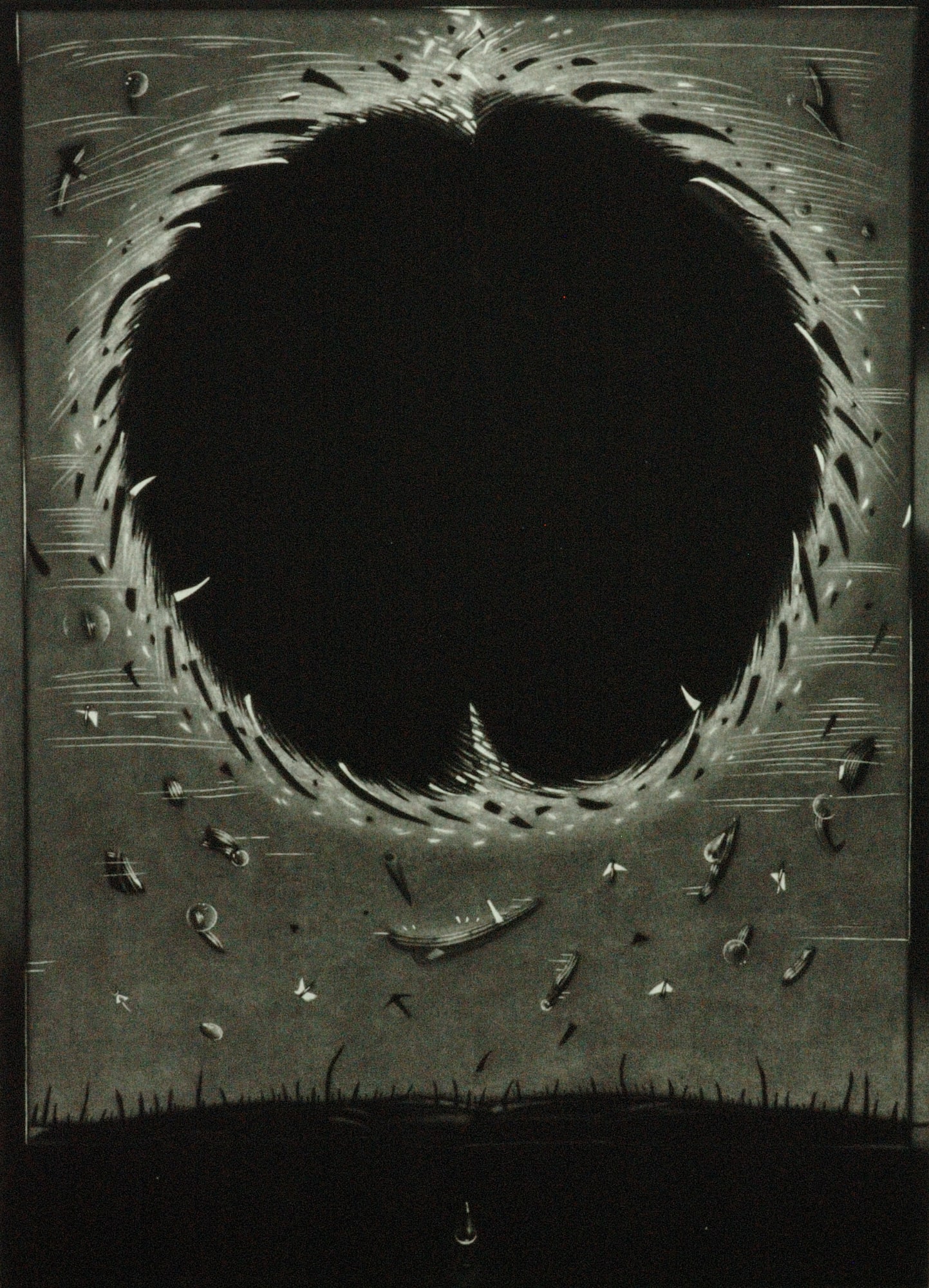

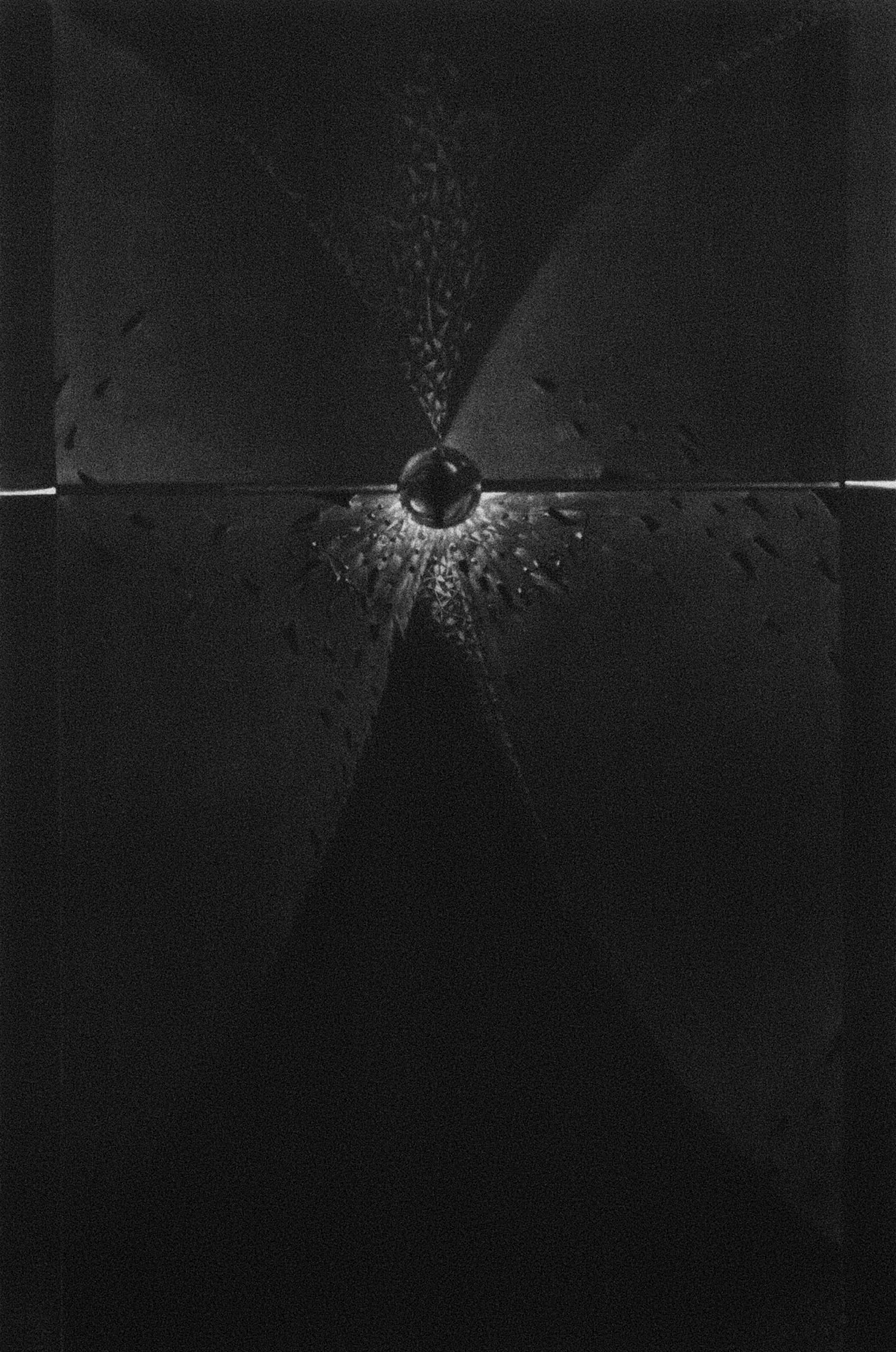

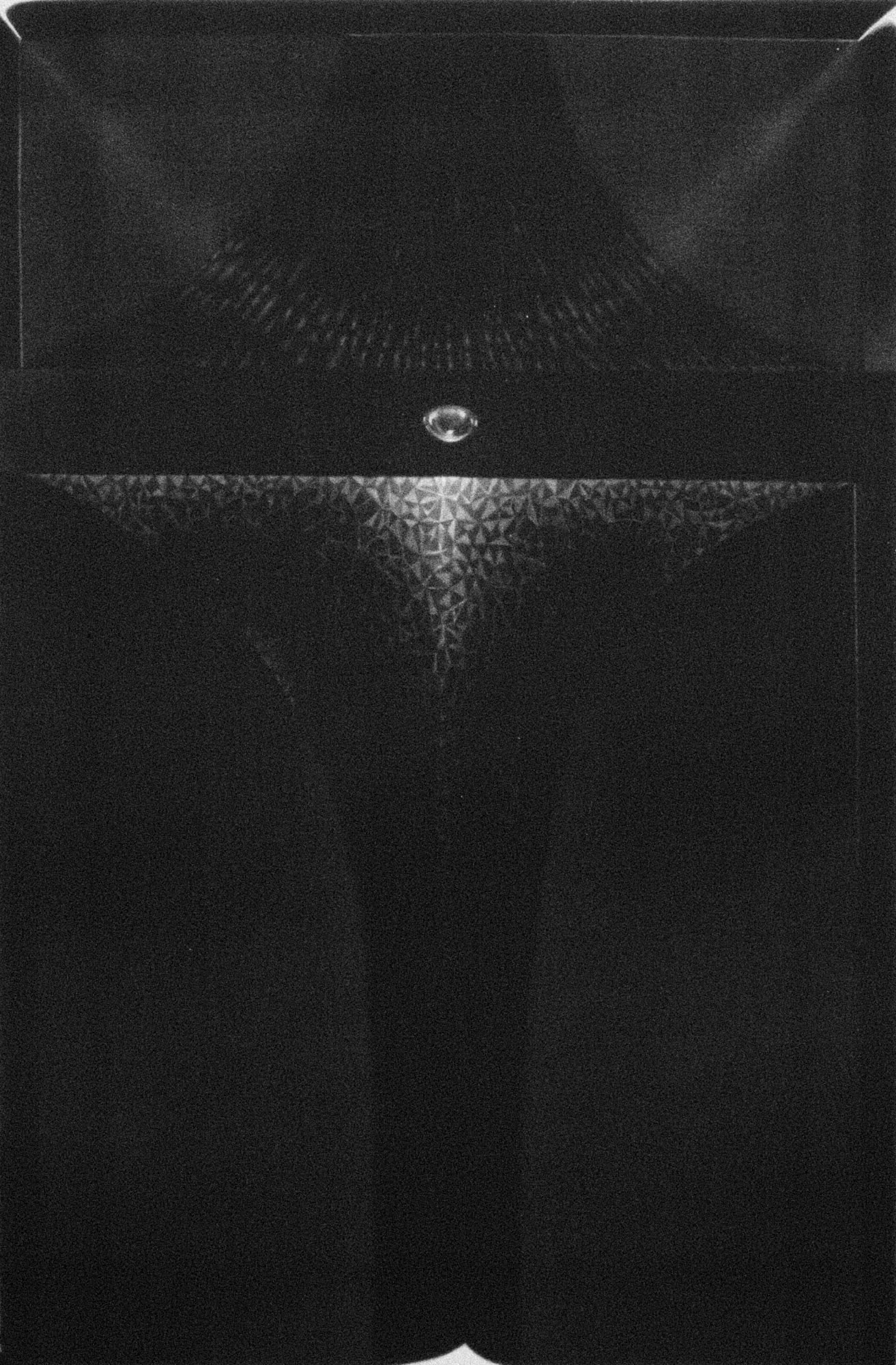

Malgorzata (Margot) Zurakowska MFA RCA, is an internationally known master of mezzotint. Inspiration for her mezzotint prints comes from ancient esoteric texts and cutting-edge cosmology and focus on light as a source of very existence. Zurakowska had dozens of solo exhibitions in Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Poland, Switzerland and the USA. Participating in over one hundred exhibitions around the world, Zurakowska has won 15 international awards, including at some of the most prestigious international biennials and triennials. Her mezzotint prints are held in the collections of museums throughout the world, including among others, Museum of Fine Arts in Boston; National Museum of Poland; Bibliotheque National in Paris; Trondheim Kunstmuseum, Norway; Museo di Arte Contemporanea, Teolo/Padva, Italy. Elected member of the Royal Canadian Academy, Zurakowska had earned MFA from the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow, Poland and followed with post-graduate training in philosophy. She has lived, and worked as an artist and educator in Poland, Canada and USA. Malgorzata Zurakowska currently resides and works in Boston MA, USA and teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design.